knowledge base

a collection of technical background of Internet censorship.

Internet Censorship

Internet censorship controls what can be viewed by a certain group of Internet users. Such information control, typically placed by authority entities such as governments, ISPs, or organizations, can be achieved by various techniques like IP-layer censorship (e.g., blocking IP addresses) and application-layer censorship (e.g., domain names based blocking in DNS, HTTP, and HTTPS), and its severity varies from country to country. This proposed research will focus on application-layer censorship, as it typically enables the censors to accurately block their undesired Internet services while avoiding collateral damage caused by prevalent IP sharing in Cloud or CDN platforms.

Application-Layer Censorship

Domain names and IP addresses are the most straightforward and useful information for censors to monitor. As CDNs have been widely adopted where the IP addresses are typically shared with many legitimate services, the IP-based blocking may cause significant collateral damage. On the other hand, the domain name blocking enables the censors to accurately block their undesired Internet services. Here, we briefly describe the application-level censorship that blocks domain names. Then, we present how a censor could be deployed and monitor the traffic.

DNS Blocking: When visiting a website, a client first resolves its domain name to obtain the network address by using DNS. Since DNS was originally designed as an unencrypted protocol, the censors on the network paths are able to manipulate the DNS responses or drop the DNS queries. Although UDP-based DNS is mostly adopted, TCP-based DNS is also inherently supported. For a TCP-based DNS request, a censor may tear down the connection with RST/FIN packets.

Domain Names Blocking in HTTP: The HTTP Host header presents the domain name a client is visiting, specifying the target service since a web server may host multiple domains. Still, the HTTP protocol is unencrypted and the censors can know exactly the requested domain. To block an HTTP connection if needed, a censor may inject a blockpage indicating that the domain is prohibited, tear down the connection with RST/FIN packets, or directly drop the request without any notification.

Domain Names Blocking in HTTPS: HTTPS encrypts all the HTTP packets after a TLS handshake so that the Host header is no longer visible to the censors. However, it is common that a web server hosts multiple domains, and each domain is associated with an independent certificate. Therefore, in order to present the correct certificate to a client before the ephemeral keys are exchanged, an SNI extension is required to be included in the Client Hello message to indicate which domain the client intends to visit. As a result, the domain name in the SNI extension is sent in plaintext and is visible to the censors. As such, to block an HTTPS connection, a censor may tear down the connection with RST/FIN packets, directly drop the packet, or inject an incorrect, forged certificate to intercept the connection.

On-path and In-path Censors

In order to examine network traffic, censorship devices can be deployed in two different ways. An on-path censor is a device attached to a router and can obtain a copy of all the packets passing through the router. Since it cannot operate on the original packets, it is unable to prevent the packets from reaching their destinations. Correspondingly, it needs to inject packets to interfere or terminate a connection. An in-path censor acts as a Man-In-The-Middle (MITM) to examine the actual packets. Therefore, it can directly manipulate or drop the packets associated with the prohibited services. The in-path device is usually hard to be identified; however, due to the capacity of operating on the actual packets, it can be efficiently detected in our proposed approach.

State-of-the-art and Significant Research

OONI: Open Observatory of Network Interference

OONI recruits volunteers to install software and manually run pre-defined censorship measurements.

ICLab: A Global, Longitudinal Internet Censorship Measurement Platform

Arian Akhavan Niaki, Shinyoung Cho, Zachary Weinberg, Nguyen Phong Hoang, Abbas Razaghpanah, Nicolas Christin, Phillipa Gill. in IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S&P), 2020.

The goal of ICLab is to develop a global, comprehensive, longitudinal censorship measurement platform, achieving mutual benefits between coverage and details of measurements. Moreover, ICLab adopts commercial Virtual Private Network servers (VPNs) as the vantage points to launch censorship measurements, including DNS manipulation, TCP packet injection, and block page redirection. The design of ICLab seeks to minimize false positives and manual effort in the process of validation.

As commercial VPNs serve as vantage points within the Internet measurement, this will reduce ethical concern of requesting sensitive content online from politically restricted regions. ICLab engages in monitoring and providing detailed data collection from all levels of the network stacks. Also, ICLab applies volunteer-operated devices (VODs) in a few locations as alternative options for vantage points. Moreover, ICLab has high capabilities to implement new measurements when new censorship techniques come out, update the URLs when needed, and re-analyze old data when applicable. The researchers collect and archive massive observations in detail through ICLab which enables them to compare the blocking techniques deployed in different regions against different types of content. The essential observation of this longitudinal measurement is that censorship consistency has changed concurrently with the political shifts. What’s more, unknown block pages and unknown forms of network interference have been detected via ICLab.

ICLab currently is focusing on website accessibility, each time the researchers only test the Alexa top 500, all of the citizen lab’s global list of sensitive websites and country specific list. Moreover, the paper displays the packet traces and mimics browser behavior as closely as the manual effort could manage to reveal what happens on the network level and application-level when a website gets censored. Finally, the researchers end up with commercial VPN as vantage points other than volunteers for the consideration of storage capacity and bandit back with consumption. It avoids the practical and ethical problems with remote volunteer work, but it means that they can only access about 60 countries by commercial VPN. There is another critical problem with commercial VPNs that they often lie about the physical locations of their servers.

In this case, Overt censorship means that the government considered a material openly illegal to their citizens thus applying restrictions for access. An end-user tries to access a censored website, she might see an overt block page that states the contract information if she wants to dispute the classification. On the other hand, she might see a completely generic error message which is saying that it tried to connect to the site and equipment and there is no detail and assertion of authority contract information could be reached. On top of that, the site is broken for this moment and it could be called covert censorship. In short, most of the cases in this study proved that the government was using overt censorship for material that was openly illegal in that country and covert censorship for material that was supposed to be allowed.

Quack: Scalable Remote Measurement of Application-Layer Censorship

Benjamin VanderSloot, Allison McDonald, Will Scott, J. Alex Halderman, and Roya Ensafi. in the Proceedings of the 27th USENIX Security Symposium, 2018.

Network filtering detection tools are currently being utilized to detect DNS and IP level interference at a global scale. Yet, there remains a large number of unmonitored types of blocking which is triggered on HTTP and TLS headers to be discovered. Analyzing the blocked keywords in this study, it facilitates building of the application-layer blocking ecosystem and comparing diverse censorship behavior from country to country.

Quack presents a remote, scalable censorship measurement framework that ensures high-efficiency application-layer interference detection. Comparatively, the authors engage in a larger magnitude experiment to test for interference across thousands of autonomous systems than in the prior work. Existing protocols and infrastructure are capable of remotely measuring network interference such as DNS poisoning and blocking between TCP/IP connectivity and remote machines. However, it is still short of a remote method to detect application-layer censorship. The prior work relies on people voluntarily involved in the experiment. Nevertheless, recruiting, maintaining, and coordinating a large set of volunteers is challenging. The design goals of Quack are detecting censored keywords that trigger network interference, minimizing risks for the safety of people in censored countries, ensuring analysis robustness techniques, and performing censorship measurement at scale.

The authors empirically define how long measurements should wait when a blocking event is incurred. Specifically, this allows ordinary servers to recover from stateful DPI disruption. In the experiment, longer timeout displays less likely to set a domain into failure due to a prior sensitive domain having triggered the stateful blocking for the given server. As such, a two-minute delay was identified as a minimum, since the system may need more time to schedule an upcoming test against the disrupted server.

Quack has been used to remotely measure network interference due to application-layer blocking such as DNS poisoning, IP-based blocking, and now application-layer censorship. The experiments regarding disruption technique detection provide insights by producing valuable datasets for political scientists, activists, and other members of the Internet freedom community. This system also can be used to reveal shifts in application-layer censorship policies. In the future, the ultimate goal is to perform application-layer censorship measurement not merely on echo protocol but also involving other protocols.

FilterMap: Measuring the Development of Network Censorship Filters at Global Scale

Ram Sundara Raman, Adrian Stoll, Jakub Daleky, Reethika Ramesh, Will Scottz, Roya Ensafi. in Network and Distributed Systems Security (NDSS) Symposium, 2020.

As content filtering techniques have been excessively utilized for Internet censorship, the censorship measurement community lacks a systematic method to monitor the reproduction of these technologies. The need for establishing effective policies calls for a careful and detailed roadmap of the state and the evolution of content filtering censorship. In early works, researchers and policymakers are merely focused on a few types of content filtering technologies that need a heavy workload for manual detection and identification. In this study, the authors present a novel framework, FilterMap, which supports scalably remote monitor content filtering technologies according to their blockpages.

The FilterMap first gathers blockpages based on filter development when performing remote, in-network censorship measurement experiments. Then the researchers observed and clustered blockpages to extract signatures for longitudinal tracking. Finally, FilterMap ensures to identify and distinguish each new blockpage, while clustering and clarifying the same blockpages based on the filter deployments. The researchers manually verified each unique blockpage to eliminate false positives. In this research, they launched two large-scale measurements either from a breadth of sensitive test domains triggering as many as content filters or from several months of longitudinal experiments to reveal the accuracy, scalability, and sustainability of FilterMap.

This study can be evaluated from the following two intervals: Data Collection and Data Analysis. For Data Collection, the measurements for massive domains on all HTTP(S) and Echo servers consume less time by sending requests in parallel. For Data analysis, FilterMap adopts iterative classification which outperforms the other collection methods by identifying 82 blockpages.

This paper has shown the most recent complete view on the deployment of censorship filters which respond with blockpages. In future research, one direction is to focus on other types of filter responses to identify filters such as the certificate returned in HTTPS measurements to further extract signatures and discover filters. FilterMap’s analysis techniques have a profound impact on eliminating false positives and reducing noise in the same sort of research. Moreover, FilterMap’s measurements inspire circumvention tool developers to develop circumvention strategies based on empirical experience. The longitudinal data collected about filter deployment can help regulate the utilization of filter technology and its illegal proliferation.

Iris: Global Measurement of DNS Manipulation

Paul Pearce, Ben Jones, Frank Li, Roya Ensafi, Nick Feamster, Nick Weaver, Vern Paxson. in USENIX Security Symposium, 2017.

Disguiser and Comparison

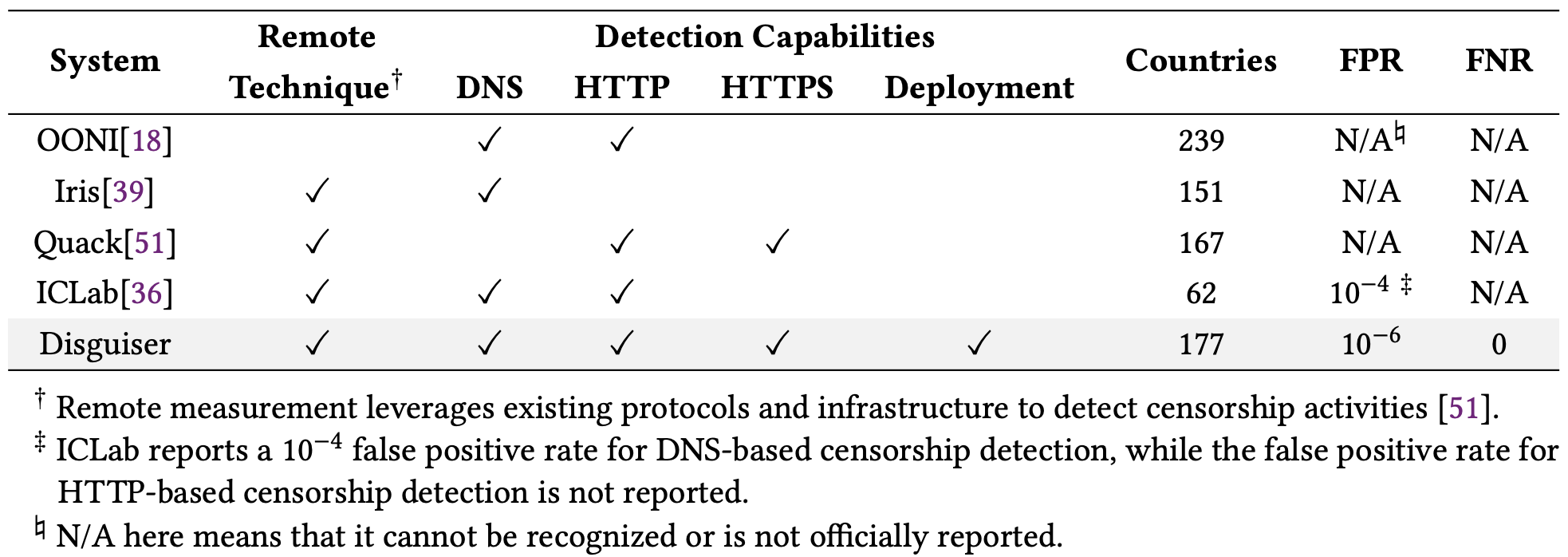

OONI recruits volunteers to install software and manually run pre-defined censorship measurements. In comparison, Disguiser and other studies adopt a remote measurement technique, i.e., conducting measurements remotely using the existing network protocols and infrastructures.

Quack leverages the Echo service that reflects back the packets sent to it to trigger censors. However, as Echo servers operate on port 7 and the Quack client runs on ephemeral ports, Quack does not generate HTTP/HTTPS traffic on their standard ports, so that it may generate false negatives when a censor only monitors traffic on standard ports. In order to compare with Quack, we operated HTTP/HTTPS on non-standard ports (including port 7 and other random ports) at our control server and issued HTTP/HTTPS requests through vantage points to our control server on these non-standard ports. Meanwhile, from the same vantage point, we conducted our standard tests, i.e., sending HTTP/HTTPS on standard ports to our control server. In the comparison experiment lasting for one week, in total, we identified censors in 32 countries that ignore the requests sent to non-standard ports but block the requests to standard ports. More importantly, many of those censors enforce severe censorship policies, including the ones in Saudi Arabia, UAE, Ukraine, Russia, India, South Korea, Pakistan, Kuwait, and Thailand. As a result, our observation shows that issuing legitimate traffic is critical to accurately detecting censorship activities.

ICLab relies on VPNs to measure censorship activities. However, VPNs are usually deployed at countries that do not enforce strict censorship policies. As a result, ICLab has a limited coverage (62 countries, less than half of our covered countries), and according to the paper, ICLab cannot observe very important activities, such as severe DNS manipulation in China, which are detected by us and previous studies. Moreover, ICLab requires conducting manual review to identify and reduce false positives and false negatives are still unidentifiable.

Accuracy

In our paper we also examine the claimed accuracy for those studies and present comparison shown below.